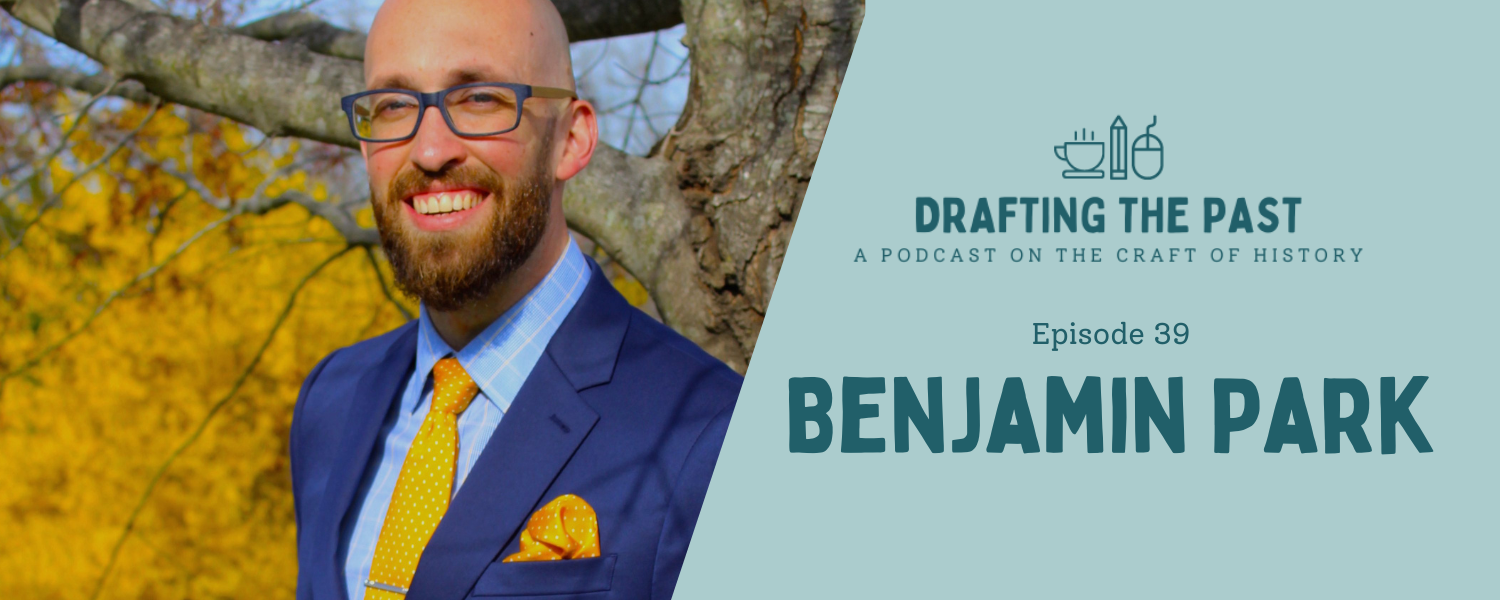

Welcome back to the third season of Drafting the Past! I’m thrilled about the lineup of historians that I’ll get to bring to you this year. I know you’re going to love them. That includes today’s guest, Dr. Benjamin Park. Ben is an associate professor of history at Sam Houston State University, and the author of three books. His first two were American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, and Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier. His newest book, which came out just this month, is called American Zion: A New History of Mormonism. I was excited to have the chance to talk with Ben about how he tackled a book with such an impressive scope, how he stays disciplined about what to leave in and what two cut, and two pieces of really excellent, practical writing advice from his editors. You’ll have to listen until the end for those.

Mentioned in this episode:

- Benjamin Park

- American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions

- Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier

- American Zion: A New History of Mormonism

- Evernote

- Scrivener

- Mormon Studies Review

- Jill Lepore’s These Truths and The Deadline

- Megan Kate Nelson, Three-Cornered War and Saving Yellowstone

- Robert Elder, Calhoun: American Heretic

- Richard Bell, Stolen: Five Free Boys Kidnapped into Slavery and Their Astonishing Odyssey Home

- Lindsay Chervinsky

- Dean Grodzins, American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism

- Joanna Robinson, Dave Gonzales, and Gavin Edwards, MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios

- Edward Ayers, American Visions: The United States, 1800-1850

Note: Book links take you to Bookshop.org. If you purchase books through these links, Drafting the Past receives a small commission. Thank you for supporting the show!

Transcript:

Kate Carpenter: Welcome back to the third season of Drafting The Past. I’m your host, Kate Carpenter, and this is a podcast all about the craft of writing history. I am thrilled about the lineup of historians that I’ll get to bring you this year, I know you’re going to love them. And that includes today’s guest, Dr. Benjamin Park.

Benjamin Park: It’s an honor to be here.

Kate Carpenter: Ben is an associate professor of history at Sam Houston State University, and the author of three books. His first two were American Nationalism’s Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, and Kingdom of Nauvoo, the Rise and Fall of Religious Empire on the American Frontier.

His newest book, which came out just this month, is called American Zion, A New History of Mormonism. I was excited to have the chance to talk with Ben about how he tackled a book with such an impressive scope, how he stays disciplined about what to leave in and what to cut, and two pieces of really excellent practical writing advice from his editors. But you’ll have to listen until the end for those.

Enjoy my conversation with Dr. Benjamin Park.

Benjamin Park: My mother would tell you that I started as a five-year-old that forced her to sit down and write stories as I dictated them, until she finally convinced me to write them myself. But in reality, I always felt pretty comfortable writing even when I got to college and I thought I was going to be a medical doctor, an orthopedic surgeon.

And I took a science class, and they had an option of either doing a science-like project or you can write an essay on some, and I chose doing the essay, and that should have been a sign, then, that that was a better course. But sadly, it took a little while for me to realize that that was my better track.

Later on, I eventually went into graduate school for religion, and politics, and finally history. And I always had a steep learning curve for learning the task of the historian, but writing was always the thing that came somewhat easy to me. I never felt like I struggled to get my ideas on a page.

My dissertation turning into a first book was a traditional academic book, so it was very steeped in the historiographical discourse. And then when I decided to write a book after that, I wanted to write for a more general audience, and that’s what led me to Kingdom Of Nauvoo, and eventually American Zion, and that was a very different type of writing task. Which I’m sure we’ll get into.

Kate Carpenter: Before that, as you know, I like to ask some practical questions about people’s writing. So let’s start by, where and when do you do your work?

Benjamin Park: I like to do my writing in the morning. I typically try to block out one to two hours every morning to write. That’s not always possible, especially as I became a parent and then took on more administrative roles. My ideal does not always match a reality, but it’s still a goal, I try to keep it.

In fact this week, even though I’m busy with stuff preparing for the book to come out next week, and for the semester to start, and some lingering administrative tasks, I’ve still been successful to carve out 90 minutes every morning just to write. And I do try to make that just writing, not reading or researching. I do that in a separate block of time throughout the week.

I try to get to a point to where I can just focus on writing for 60 to 90 minutes. I try to get between 750 and 1500 words down during that time. And I’m one of those to where I can’t really lay my head on the pillow at night unless I’ve written a few hundred words that day. So it’s probably an issue with me, but it’s at least helped me be productive in that regard.

So I try to do writing in the morning. When I do see the end in sight for certain projects, if I’m nearing completion of a chapter or a book, it becomes all-consuming. Then I’m staying up late at night, writing. I find pockets of time to write in the afternoon, but that’s usually a rare occasion. More so, I try to confine my writing to an hour and a half or so every morning.

Kate Carpenter: How do you organize your sources and the materials you use in that writing?

Benjamin Park: Yeah, I take all my notes in Evernote, which is a note processing software program. I typically have different Evernote pages for every archival collection. If it’s a huge collection, I’ll break that out into more. And then I have all those different pages organized through tags and folders, according to usually assigned to a specific chapter within a project. And then I’ll do tags that have sub-sections within that chapter.

Because what I want is, when I get to my writing time, I can just have all those pages up on my dual-screens, and just write without having to search for things. And I usually go through, and the night before I do writing, I’ll read through the sources that are relevant to whatever the next day’s writing session is going to be.

And I will highlight quotes that I think are going to be crucial, because I don’t even want to waste my time searching for those quotes the next day. I want them to pop out with color, if possible.

And I do my writing in Scrivener, another writing software. Because I find it useful to be able to jump back and forth in different chapters, different sections, without much difficulty. And I’m one that, I bounce around my chapters as I write. I don’t write from beginning to end.

I found that for me, I am most productive when I write according to my interest. What is drawing my fascination at this moment? Where is my passion? And that’s what’s going to write.

So for instance, my book American Zion, I started with chapter five, because that was the period that struck my fancy when I started writing. And then I wrote from chapter five to chapter nine, then I went back and did chapters one through four, and then I wrote the last chapter for final.

So yeah, in a way it’s madness of just, sporadic moving around. But I do promise there is a bit of method there, at least one that makes sense in my mind.

Kate Carpenter: I’m always curious, when you say you organize your sources by chapters, do you have a sense of what the chapters are then, before you start writing?

Benjamin Park: I do. I typically, when I set out on a project, I will map out and I will have an outline in my Scrivener document where, these are what the seven chapters are going to look like. These are what I think the subsections might be, and the themes, those frequently change.

I’ll even go so far as listing, this is when I’m going to introduce this character; in chapter two, subsection three, and then I’m going to carry this character to chapter five. And sometimes I’ll have those writing boards out with timelines, so I can see.

So I do start out with a bit of structure, but they end up being very loosely-held. Because I often change the chronologies for the chapters, the themes for the chapters as I move along.

In fact, I’m just hitting this realization that the writing project that I’m working on right now, I had plotted out six chapters. And I’m in the first stages of writing it, and I already know that chapter three is going to be broken up into two chapters. And I’m fine with that.

So I start out with what looks like some strict structure, but it ends up being quite porous.

Kate Carpenter: Where in your research process then, do you start that outlining and writing process?

Benjamin Park: Very early. I sketch out an idea of what the project’s going to be like from the very start, and then I dig into a lot of research. And I will go quite a bit of time without writing a lot. So I just finished a five-month research fellowship out in Boston, where I was writing very little because I was in the archives, researching every day.

Now I will, every once in a while, when I stumble upon a number of documents of the archives that I feel really speak to me at a certain moment, or that I’m really excited about what I’m stumbled upon and what the broader lessons are, or I get a narrative device popped in my head, I will bring up the Scrivener document and I will write 700 words on that.

And so, if you were to look at the Scrivener document for the project I’m working on right now, I have several sections of chapter one written out. Nothing in chapters two through four, and then three subsections of chapter five drafted out. Because I thought that those documents, when I came upon them in the archive, they’re so riveting that I stayed up a couple of consecutive nights to write out what that could be.

And I’m also very fine with none of that end up making the final project. Because I might not end up covering that topic in the book, or I might have to condense it down quite a bit. That’s fine. I’m more dedicated to the process of writing and continually being in the mode of making written arguments than I am being fast.

And so I really think as long as I’m in the mode of writing, it makes the revision process, too, a lot easier.

Kate Carpenter: Talk to me then about what your revision process does look like.

Benjamin Park: My revision process evolves during a project, and it’s very different according to the different chapters I write. My early chapters I typically write end up being horrible. In part because I’m just getting into the project, I may not know all the secondary literature yet. I’m still doing further research. And I, to be frank, don’t know what the book is quite yet. I don’t know what the overall argument is.

But I think it’s important to get that crappy draft out first, of those first few chapters, because that’s what gets my thinking going. And then as I move along to the different chapters, the ideas crystallize into better form. And I know what I’m doing, and I know how to do it.

And so I realize, okay, this is how I need to go back and revise those first few chapters. So by the end of the writing project, my latter chapters don’t require that much revision, because I’ve gotten to the point to where I have a vision for what the book is by the time I write those chapters. But I do have to go back and revise the earlier drafted chapters to fit what this new project is.

And then once I have a whole manuscript, and this has been the case for everything I’ve written, I’m always way over word count. Which requires me to go back, and I will do a full read through of the manuscript. And I will make notes, on this section is bloated, this chapter is missing X, I need to carry this through line here. And so I’ll go through and do more substantive revisions throughout.

I wish I could say I was old-school, and I printed out and I have handwriting in the margins. I’m not that way. I’m all digital. So I will look through it in Word, I’ll take notes on my phone, and then I’ll go through and I’ll revise it in Scribner.

Kate Carpenter: You mentioned that this is your third book. I’m curious to know, has this writing and research and revising process changed for you over time?

Benjamin Park: In a way, the foundation of it is still there. I still have the same type of approach of doing a lot of research, but writing a little bit along the way, and then fully engrossing myself on the writing project and then the revision process I mentioned before. That’s mostly the same.

What has changed is, I feel a lot more confident in the process now. To where, I don’t have to pause as much whenever I feel like I’m in a rut. I know, okay, just pick another part of the book and write about that.

I’m a lot quicker in getting my words on the page, and I’m also much less reluctant at revising stuff. I’m perfectly fine with realizing, this section is crap. I’m going to scrap most of it and rewrite it. Whereas for my first book, I was worried if I deleted a section of a chapter, that’s going to be gone and I’m never going to fill it again, because it was so hard to write each and every word of that.

To where now I feel much more comfortable to where, okay, I can delete these 800 words, because I feel pretty confident I’ll write 800 better words tomorrow. And that’s a liberating feeling that brings a lot more confidence during the writing.

Kate Carpenter: American Zion is, the subtitle is, A New History of Mormonism. I know you note in the introduction that it’s not a comprehensive history, because that would be a massive tome, but it is a very broad book. There’s sort of a hint in your acknowledgements that this project was maybe pitched to you. So I’m curious to know how it came about.

Benjamin Park: Yeah. The day my book before this came out, Kingdom of Nauvoo, the press approached me. So that was published with Live Right, an imprint of WW Norton. The press approached me and said, hey, what would you think about writing a general history of Mormonism?

And at the time I demurred. I wasn’t that interested in it for a number of reasons, I was already starting another book project that I was excited about, and then a couple of things happened that changed my mind.

The pandemic hit, this was in spring of 2020, which meant that archives were going to be closed that I needed to research in. And I also took on an administrative role at the university, that meant I wasn’t going to be able to get the sabbatical that I was hoping for to be able to do the research. So suddenly I was in need of a project that I could primarily write from my office.

And writing a general history of Mormonism allowed me to do that for two reasons. One, it’s based on a lot of secondary literature. And I know a lot of the secondary literature already, so it wasn’t a steep learning curve, although jumping into the 20th century was a bit daunting for me at first.

But second, this was a topic to where so many primary sources related to Mormonism are available, digitally. Both those that have been published as part of documentary history projects, which Mormon history is proliferated in, or a lot of just primary sources that the LDS Church archives have digitized back in Salt Lake City. I forget the exact number, but they say they digitized something like 2000 pages of documents a day there.

Kate Carpenter: Wow.

Benjamin Park: And you can always request, there’s a source that they haven’t digitized and you want to see, you can put in a request. And I’ve had one experience where I put in a request on a Monday, and by Wednesday I had scans in my email about those sources. So this was a project I took on at the request of the press, because this was something that I could write during a pandemic.

Kate Carpenter: That’s really interesting. I am struck by how many books that are coming out now were really shaped by what was available during the pandemic, and what was a manageable project.

Manageable is perhaps a funny word for this book, because it is very broad, both in time and topic. In fact, you call it a fool’s quest in the acknowledgements, which made me laugh. So how did you get your mind around that kind of scope?

Benjamin Park: It really is a fool’s quest to cover 200 years of a religion that has 17 million members across the globe. That has such a large historiography, that I have book cases full of books on this topic. So every paragraph in my book can and has been expanded into entire book projects.

So I should state from the outset, it is a stupid idea to write a book like this. But I figured that there was a lesson that I wanted to take out of it, or an overall message, an argument. And so once I chose what that central argument was, that dictated what I’m going to be writing about, what characters I’m going to be researching.

And there’s tons of fascinating topics, and individuals, and texts that I could have wrote about. But if they didn’t fit this overall argument, I don’t have time for that. And so as a result, I had to be very disciplined. And that was helpful, because it made an impossible task a bit more possible.

Kate Carpenter: Was it challenging to leave those things out? I mean, did you sort of wrestle with not including things?

Benjamin Park: Absolutely. I mean, I had whole subsections that I ended up having to cut because, just due to space. I mean, when I initially envisioned this project, I planned 10 chapters that were 15,000 words. And my first drafted chapter was 30,000 words. And so I knew I was in trouble. And my press didn’t want to go any bigger. Because they rightly were like, we think we can sell it at a certain price point, we don’t want to go beyond that, so we need to stick to the word count.

And so yeah, it hurts me on two levels. One is, lots of phenomenal stuff I want to cover. And I feel like the story’s incomplete without it. Which is why I bend over backwards emphasizing this isn’t a comprehensive history, yada, yada, yada.

But on another level, I also know I’m going to get reactions from people who are like, well, why didn’t you cover this? Why didn’t you detail this? Why didn’t you engage my book, or talk about my ancestor, or my pet topic?

I remember once at a book panel at Organization of American Historians where they were discussing Jill Lepore’s These Truths, or her massive history of the United States. And David Hollinger in his critiques said, “All right, before everyone starts teeing off in the Q&A about, why didn’t you cover this topic? Just keep in mind, every single word you would put in this book would require taking out another word.”

And so having that mindset was quite crucial to me.

Kate Carpenter: That is helpful. So I want to talk a little bit about your own relationship to this history. Because you talk about it right away in the prologue, that your own relationship to the Mormon faith, and the way your understanding of its history changed as you grew and as you studied history.

As a historian and a writer, how did you think about your relationship to the story as you were researching and writing?

Benjamin Park: Yeah. I am one that, in the past, has been very reticent to talk about my own background. Especially my affiliation to the Latter-Day Saints Church, because it’s a charged environment. History means something to Latter-Day Saints. For many, history is a replacement for theology within Mormonism. So when you challenge historical truths, you’re challenging foundational bedrock for the faith.

And so this has resulted in a number of major battles over the years over how to talk about its faith, or the history, and how it relates to one’s faith. So I’d always been quite reticent. My editor, very wise editor, Dan Gersal, he emphasized that, this is all great. But it would be great for you to throw a little bit of yourself in there.

So my first draft of the introduction doesn’t bring in me at all. It just talked about the past. I didn’t want to talk about my own relation to it at all. Because I’m like, I want people just to read not knowing what my relation to the story is.

And then my editor very sneakily said, “Well, why don’t you add a little coda at the end of the prologue, kind of just talking about where you’re coming from?” And I’m like, all right. So I wrote a few lines there.

And then the next round of revisions, and we revised the introduction no less than 15 times. And then the next round of revisions he said, “Well, why don’t we take this paragraph from the very end and move it to the very beginning? And expand it a little more?”

And so, little by little, he was able to pull out more and more. Because he was right, it is helpful to know where a historians come from. Now, there are lines, boundaries for me on that. Because I talk about how I was raised in the Latter-Day Saint Faith, that I attended BYU. And it was my experiences at BYU that led me to reconsider some of the historical aspects of my faith, the faith of my ancestors.

So I talk about that interest, but I’m also too concerned about highlighting how that ends up framing or dictating my arguments of those in the past.

So one example would be, Joseph Smith claimed to unearth golden tablets in upstate New York that he then translates into the Book of Mormon. And that these golden tablets were passed down from ancient Christians who lived on the North American continent.

Now, those outside the Latter-day Saint tradition are going to notice the fanciful nature of that story, and will expect the historian to at one point, at some point take off the mask and say, all right, what really happened here? Was he refashioning a thing of tin? Was it all just made up in his mind? Did he encounter printing plates that he’s now passing off as some antiquitous records?

And I think that’s not outside the boundaries for a historian to cover, but I also think it can get distracting. And so instead, on a lot of those occasions, I grant epistemic sympathy to my characters. Where I’m like, all right, let’s talk about it from the perspective of the believers, of why those gold plates were so crucial. And then why they were seen as heretical by those outside.

And so in a way that’s sidestepping the issue, and I recognize that some might see that as cowardly. But I also think that to foreground the debates over things like historicity or the divine nature is going to turn off a lot of readers, especially when the goal of this book is to explain the broader cultural impact and context of Mormonism, rather than getting into the niceties of their historical claims.

Kate Carpenter: To give us a chance to explore how Ben tackles some of these questions on the page, I asked him to read an excerpt from his new book, American Zion. Here’s Dr. Benjamin Park reading from chapter one of American Zion.

Benjamin Park: “The highlight for Joe Smith Jr on April 6th, 1830, was not when his new church, the Church of Christ, was officially organized near Fayette, New York. Nor was it when he was sustained by the 40 or so attendees as the faith’s first elder. It was not even when he received a new revelation that declared, in God’s own words, that he shall be called a seer and translate and prophet and apostle of the church of Jesus Christ. Such revelatory texts were common by this point.”

“The highlight came when Smith saw his father’s six-foot two frame emerge from the water, a baptism that signified the aged seekers’ religious commitments, an ordinance that made his family whole. The younger Joseph embraced Joseph Sr as soon as his father exited the water, still dripping. Joseph Jr was two inches shorter than him, and had a full head of brown hair, a large nose, and heavy eyelashes. Neither man could keep his composure.”

“Oh my God,” the son exclaimed. “I have lived to see my own father baptized into the true church of Christ.”

“Lucy McSmith, mother of the prophet and wife of the baptized, later recalled that Joseph Jr buried his head in his father’s chest and wept like an infant. “His joy seemed to be full,” a fellow participant noted.”

“The emotional scene was the culmination of decades of events within a single household. Just a few years before, the Smiths were a family divided by religion, beset by financial difficulties, and faced with an uncertain future. Now they shared a singular belief, were united in purpose, and claimed a network of supporters.”

Kate Carpenter: Beginnings are important for writers. And they’re tricky to figure out, where’s the best place to start? And in a book like this, there are so many places you could have started, whether that was Joseph Smith Jr’s birth, or the first Revelation, or any number of places. Why did you decide to start here?

Benjamin Park: I think there are two reasons. One content-focused and one stylistic focused. The content focus was, the goal of that first chapter was to explain how, what was first a family seeking for religious unity, resulted in a new church.

Because we now look at the church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints today, a global religion with millions of members in many nations across earth, and just assume that it’s always been a big corporate institution. But Mormonism began as a family faith, so I wanted to emphasize the familial dynamics at the heart of it. As well as emphasizing the human nature of it too. It’s not a revelation or a scriptural translation that I wanted to begin with. I wanted to begin with a father and son embracing after a baptism.

The stylistic reason was, I wanted to demonstrate from the very beginning that this was going to be a character-driven story. That this was something that, we’re going to see emotions, and passions, and triumph and disappointment, and things that drive the human existence, rather than the church as an institutional, corporate, kind of non-human entity. I wanted to make sure that people knew that we were going to be getting three-dimensional humans in the story, not just ideas and ecclesiology.

Kate Carpenter: This scene when I first read it seems pretty straightforward, as this just description of what’s happening. But then when I read it again, you really see how layered it is with details and background information, so that the reader knows what’s happening, knows who these people are, and the significance of this moment. How did you think about pulling this opening together and layering that in?

Benjamin Park: I had to center, what was the main message I wanted to take from this? Because even though I desire to pack this book with lots of anecdotes, and character development, and plot lines, it couldn’t be story just for story’s sake. It had to capture both the relevance, but also the context.

So in this opening scene, I wanted to make sure to emphasize the emotions that were at play. That Joseph Smith was an emotional individual. And that much of what’s driving his religious innovation was an anxiety to bring familial harmony. He’s wanting to make his family whole, because his family had been divided into different churches.

And so that’s a very humanistic reason to do things. And so, I wanted to foreground that. I also wanted to make sure to paint several characters at the scene. Lucy Mac Smith, Joseph Smith Jr’s mother, she’s a key player in the first two chapters. So I had to get her in somewhere, even if that meant just her reciting her reflections from later on.

I also wanted to get a perspective from someone who wasn’t a member of the Smith family, but was one of the many people who were going to be following the Mormon religion soon after, which is why I quote one of the other participants.

And then I needed to summarize it all in a punchy way of how that highlights the growth that you’re expecting to see in this chapter. Those final few lines and that introduction, I cite that a few years before the Smith family was struggling, they were divided. They didn’t have much of a future. Now they had purpose, they had followers, they had religion.

And in a lot of my chapter introductions, you’ll see those kind of signposts that I’m hoping readers will pick up as they follow along the story.

Kate Carpenter: We’ve already discussed the huge scope of this book, and it takes a massive amount of both secondary and primary sources. But you do such a great job of creating a narrative here, in which your sources get out of the way. You’re not bogged down in references, or in this sense of material. How do you make that happen on the page? Does it take revision? Does it come out naturally?

Benjamin Park: It takes a lot of revision. And I will say, I learned a lot of the lessons from when I wrote Kingdom of Nauvoo. Because when I wrote Kingdom of Nauvoo, that was the first time I wrote a book that ended up being with a trade press rather than a university press. And I thought I knew how to write.

But it was the wonderful Bob Weil, who was the editorial director at Live Right, who gave me a line-by-line breakdown of my manuscript. Every single line in the manuscript had black in it from his markings. And I realized that to write a narrative that’s going to be gripping to general readers, you have to write it differently than what you would write for fellow academics.

First of all, you don’t engage historiographical debates in the text itself. That’s just not, you don’t have space for that. General readers don’t care. So I move all of that to the footnotes.

In fact, there’s a general trend in my writing to where, when I’m writing a draft, I’ll engage secondary stuff in the main text, and eventually I’ll move it to the footnote. Then often I delete it from the footnote in total, because my project just can encompass all those historiographical works. So, can’t engage secondary topics.

And then further, I looked at writing this type of work, that is more of a synthetic overview, much closer to classroom lectures than an academic article. What is the arc going to be? What are the key points? You might have some ideas, or characters, or arguments that you think are fascinating, but is it relevant to the story? Is it moving the narrative along? Because if not, you cut it.

And so keeping the focus. And I will say, another tool that I found that was quite useful was when I started writing Op-eds for newspapers and magazines. Because that taught me the tools to digest large amounts of information in a very informative and efficient, compact argument.

So recognizing how to decipher what matters here, and to leave everything else on the cutting room floor, it’s hard for historians who are used to making arguments. But it’s necessary if you want a compelling narrative.

Kate Carpenter: What drove you to be interested in writing for a more public audience?

Benjamin Park: Yeah, it’s hard for me to point to one thing. It was something that I was always interested in. Even when I was an undergraduate student, I started writing some op-eds.

Now, most newspapers and magazines weren’t interested in publishing me at that point, but I tried. And because I felt like history had a lot of lessons and meanings that the general public was missing. And at least for me, it was a way to justify this career choice. Because it proved that doing history matters.

And now, that’s not to say that historical work not written for a general audience doesn’t matter, because that’s absolutely not the case. I mean, my book on American Zion would not exist in the state it is if it wasn’t for the mounds of scholarly research that was written primarily with other scholars in mind.

So I think it’s recognizing where your particular strengths are, and what you feel you can bring to the table. And for me, I felt like I can condense and digest information in a narrative a lot better than I can make these nuanced and careful historiographical interventions that I deeply respect other historians doing, but I’m maybe not the best at doing myself.

Kate Carpenter: You also are very active on the academic side. You’re an editor of the Mormon Studies Review. How do you see that work and its relationship to your writing?

Benjamin Park: Well, I think it goes hand in hand, because scholars have to be able to converse with one another. I am a full-fledged apologist for academic work for academic sake, because that’s how a discipline grows.

And so the Journal Mormon Studies Review that I’m a co-editor on, that’s very internal discussion. I mean, we are writing for other scholars on, what does this intervention tell us about modern conceptions of secularism? My mom is not going to be interested in that kind of discussion, and that’s fine.

I think we need to lose, sometimes, this anxiety to say that unless you can explain this to the broader public, it’s of no use. For me, it was very useful. Because editing this journal for the last few years, it made me aware of all the scholarly developments that I can then take and write my broader narrative.

Because when you write a general synthesis or a popular history, if you’re not grounded in the historiography, it’s going to be rootless. It’s going to be untethered to the actual discipline. And I think we can all think of certain books that are written without that broad base, and that suffer as a result.

Kate Carpenter: I noticed in the acknowledgements, I think you thank a writing group. And I was curious, what other people do you rely on for feedback on your work?

Benjamin Park: I have a wonderful writing club that includes a number of historians who write for both general and academic audiences. Megan Kate Nelson, whose wonderful books on the American west, Robert Elder, who wrote the great biography of John C. Calhoun, Richard Bell, whose book, Stolen, on the five African-American boys who were stolen into slavery from Philadelphia, is a classic. And Lindsay Chervinsky, who is one of the best public historians out there.

We meet monthly, discuss each other’s writings, ask for progress. And I love that type of community. I also have a wonderful department, to where we do brown bags and discuss each other’s chapters, and that’s really helpful too.

When I write a book that’s as audacious as American Zion, I rely on lots of other people to give me feedback. So each of the chapters that I finish, I would send to five to eight people who are experts in that era. And I beg them to let me know, what am I getting egregiously wrong? And often, I do get things horribly wrong and they save me from myself. And so I’m a big fan of getting feedback from other scholars.

Kate Carpenter: At what point in the writing do you like to get feedback? Is there a point where it’s unhelpful?

Benjamin Park: Yeah, I think there’s different types of feedback that are useful at different points. So I’m currently embarking on a new research project on religion and the abolitionist movement in 1840s, 1850s Boston, with a key focus on a figure named Theodore Parker, who was a very prominent abolitionist minister during that time.

And the best feedback I’ve received at this point is a wonderful and kind scholar by the name of Dean Grodzins, who wrote a biography of Theodore Parker. I would have a number of lunches with him, where I just pick his brain on ideas that I’m still in the early process and he’s able to help me.

And I wasn’t revealing too much of my stuff, I’m just having ideas and he is helping me think through it. Once I finish a few chapters, I’m going to … As soon as I finish a full chapter draft, I send it out to people. Because I want to get thoughts.

Especially early on in a project, I will send a chapter draft out to someone who may not even be an expert in the themes or topics that are discussed in that chapter, just because I want them to read, does this chapter make sense? Does this argument come through? And then once I get feedback on things like that.

Then I’ll start just sending it to people who are experts on the fugitive slave law for my chapter on 1850, and make sure I get those right things.

So I send out chapters at a time. I am not one that waits until the end and sends an entire manuscript to people. Because I know if I send someone an entire manuscript, A, they’re not going to do it. And B, I would feel guilty asking people to do it. That needs to be a press sending it out and paying them for that. So I like to send out chapters and getting the feedback that way.

Kate Carpenter: Who do you read for inspiration, or maybe there are other forms of media that you like to listen to or watch?

Benjamin Park: I typically like to read good, gripping nonfiction before I go to bed every night. Because that at least puts me in the mood for, what does a story develop? And it doesn’t even have to be history.

I recently read the new book by Joanna Robinson and a couple of co-authors on the Marvel Cinematic Universe in America. And the way that they’re able to tell the backstories of Hollywood maneuvering, and actors’ demands and things like that in a gripping way, I loved. And so I take ideas from that.

I love reading personal essayists. Jill Lepore’s recent compilation of her New Yorker essays as currently on my book stand, that’s what I’m reading every night right now. I find that very useful.

I have a long commute, and so I listen to a lot of audiobooks. And those audiobooks are typically popular histories that help me understand how to condense broader topics into a good narrative. So I just finished the audiobook of Ed Ayers’ new book on American Visions, and that was one good example of how to use characters and anecdotes, which that book succeeds at.

So those are a few examples. I like to, for inspiration for writing, I read a lot of historians. I’m not one who reads fiction, it’s just not my wheelhouse. I know it’s helpful for some people, it’s not for me. I read a lot of popular histories for inspiration for writing.

Kate Carpenter: What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever gotten?

Benjamin Park: Oh gosh, two. I have two writing advice. And one came from Bob Weil, who was my editor for Kingdom of Nauvoo. And he told me to remove 70% of my quotations in my book. Which is hard for historians, because those are our receipts, as the kids call it, right? This is our evidence to make our argument.

And he emphasized, quite rightly, that this book has to be in your voice. It has to be your narrative. Otherwise, people are going to get tripped up. And so learning to rely on my voice rather than the voices of my historical actors was really, really good advice.

A second piece of advice is my most recent editor, Dan Gersal, who told me to treat every chapter like a short story. There has to be character development, there has to be a plot arc, there has to be a question that is asked in the introduction and is not answered until the end. There has to be something that keeps your interest.

And breaking up the broader book into these shorter stories, I find, makes all the difference.

Kate Carpenter: That’s good advice. Those are ones I haven’t heard yet on the show, so that’s great.

So you already mentioned what you’re working on next, so I’m going to ask you a different closing question. Since we are doing this interview in January, I’m curious, do you set writing goals for the year?

Benjamin Park: I don’t. I mean, I do have goals for writing books, and so I have deadlines to turn in this current abolitionist book to a press that I hope to do. And so I do set goals, but it’s not like, word count. And I will say, it’s not even that firm.

So for the book I’m currently working on, I have a soft goal to have the manuscript done by January of 2025. But then I have a realistic goal of having it done by August of 2025. So I have both the optimistic goal and the realistic goal.

And sometimes optimistic goal works. I was able to reach my optimistic goal for my American Zion book, so I actually turned it in a number of months before my contractual deadline. That’s not the case, always. And so I think my editor said that I was one of the first academics who actually turned in before deadline, so I’ll take pride in that.

But I also realized that certain circumstances broke in my favor that year that enabled me to do that, and that’s not always going to be the case. I now have a kid who’s in high school, I have to take kids to swimming practice, and so there are realities that get in the way.

So I do have strong commitments, but they’re loosely-held. And I am totally fine with revising them.

Kate Carpenter: Excellent. Dr. Benjamin Park, thank you so much for joining me on Drafting The Past and talking about your work.

Benjamin Park: This has been great.

Kate Carpenter: Thanks again to Dr. Benjamin Park for joining me on Drafting The Past. And thanks to you for listening.

Obviously, I love talking about writing craft, and this year I’m trying to do that even more. Through the Drafting The Past newsletter, you can expect to find deeper dives into writing techniques, interviews with editors, and maybe even some peeks into my own research. You can sign up for the newsletter at draftingthepast.com.

While you’re there, you can also check out show notes for this episode, including links to all the books that Ben mentioned and a transcript of the episode. Until next time, remember that friends don’t let friends write boring history.